Personal Knowledge Management for Minimalists

I'm finally saying goodbye to PKM. Here's why.

Would you believe me if I told you I’d stumbled across a single solution for at least four of the neurotic preoccupations that trouble lifelong students like you and me? In fact, It’s not even a solution — it’s a simple change of mindset that can be implemented immediately and might save you from a tonne of wasted time, soul searching and mental gymnastics.

The False Promise of PKM

A little context first. I am not a professional writer or academic, although at times in the now distant past I have aspired to be both. My interest in studying, learning, reading and writing is driven by pure intellectual curiosity and a strange compulsion to understand everything. Even now, as a middle-aged dude with a fair bit of study under my belt, I have more questions than answers. And that’s how I want it to be; I have no desire to one day ‘be done’ learning.

Anyway, that’s why I read, write and, at least until this week, made notes.

Adults can be classified into three buckets in terms of the note-making habits:

Doesn’t make notes at all

Scribbles things down on bits of paper and in the notes app on their phone; never looks at them again

Orchestrates a complex paper or digital system of hundreds or thousands of notes; implements complex workflows and techniques; spends hours curating and developing their system; never looks at them again

The rabbit hole that is (3) is known as ‘Personal Knowledge Management’ or PKM. If this concept is new to you, then this essay might still be an interesting read, but is going to sound like calling for a nuclear strike on Mothers’ Union gathering. If you’ve been down the rabbit hole, or are perhaps still down it, you’re either going to love me or hate me with a passion.

For me it started with Thiago Forte’s book Building a Second Brain (BASB), a classic springboard into the world of PKM. From ‘BASB’ I delved deeper, scouring the forums and consuming hundreds of hours of related content on YouTube. I read Sönke Ahrens How to Take Smart Notes, learned about Zettelkasten — the mythical method that made Niklas Luhmann “extraordinarily prolific”, explored the concepts of Atomic Notes and Evergreen Notes, read books about how to read books (!), tried countless PKM apps including the heavy hitters like Logseq and Obsidian, as well as just the vanilla Apple Notes app on every iPhone, tried at least 8 different read-later apps like Instapaper and Pocket, paid for subscriptions to ‘retention’ platforms like Readwise and bought and sold electronic devices like eReaders, tablets, styluses, scanners and recorders. I’m ashamed to admit this but I even watched videos where people try out different pens and coo over the smoothness of the ‘gel flow’. That was my low point (if you don’t count endlessly exporting notes from one app, importing them into another, only to re-import them into the original app two weeks later).

If you’re still with me, I’m guessing you and me might have just a little bit in common.

I did all this for two reasons. Firstly, I love a geek out and this kind of stuff just appeals to me. I’m happy to admit that. I’ll also admit that it mostly made me depressed. I never found a system I could stick with. The story was always the same: create an unmanageable amount of complexity that kills any joy in the process and then try to revert to something simpler. Secondly, and more importantly, there was an implicit promise in PKM which I now take to be false. Don’t get me wrong, this is no-one in particular’s fault — it’s a heady mix of marketing copy, click-bait titles and probably a lot of personal insecurity.

Let’s take a brief look at some of the headline claims made by players in this space without naming names:

“A proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential”

“Combine timeless notetaking practices with modern digital tools to finally get organized and create the life you want”

“Makes it easy to revisit and learn from your ebook & article highlights”

“Save all of the interesting articles, videos, cooking recipes, song lyrics, or whatever else you come across while browsing”

“Save everything to one place, highlight like a pro”

“Gives you the power to organize and connect these ideas in new ways”

“Gives you the tools to come up with ideas and organize them”

“Invent your own personal Wikipedia”

I could go on, but the pattern is basically the same: organise, save forever, become magically productive. PKM is supposed to make your knowledge permanent and organised in such a way that it leads to effortless output, just through its very existence. Logseq says it “helps you organize your thoughts and ideas so that you can come up with new outputs more easily”. For convenience, let’s encapsulate these ideas with the word ‘productive’ which is, I think, as close to the general gist as we can get with one word; productive in the sense of ‘creating more output’. Output is key here.

PKM promises to make you more productive, and for me, at least, I now think the reverse is true. The rest of this article explores why I now think the promise of PKM is a spanner-in-the-works for non-professional scholars like me and what I’m going to replace it with.

Notes Are a By-Product

Have you ever read or watched something, or heard someone say something, that somehow gave you permission to give credence to that secret, nagging belief that’s been hanging around in the darkest recesses of your mind?

About a month back, the YouTube algorithm, in its infinite wisdom, started teasing me with videos about people deleting their second brains. The first time I saw the thumbnail for one of those videos I did a double take and then immediately felt a wave of relief and the immediate urge to go up to my desk and trash my own vault. I felt joy. I felt free. I felt unburdened — and I hadn’t yet even watched any of them. It’s OK, I thought, to hate this shit. Nothing really changed though, until I came across the work of art that is Andrew Adriance’s Second Brains are a Lie. Watch it. Twice. There are so, so many nuggets of truth in this beautiful takedown of PKM, and in this section we’re going to go pretty deep, but let’s start with a selection of quotes:

“Knowledge does not equal wisdom”

“Knowledge needs purpose”

“Knowledge is helpful, but only when it’s serving a cause”

You can only truly understand the force of this argument if you are familiar with how the False Promise of PKM works. It goes something like this: you collect and curate a permanent digital vault of interconnected notes (the so-called ‘second brain’) from which inspired new ideas and output arise. For academics, content creators or writers, this output might be articles, books, videos or software, but for the serious lifelong learner I now understand this output to be wisdom. The knowledge itself is not wisdom, it is just a collection of facts. We arrive at wisdom (hopefully) through this knowledge, but the path is not straightforward. Wisdom does not simply emerge from a beautifully tagged and categorised Obsidian vault. In fact, in my experience, and I am manifestly not alone in this, nothing at all automagically emerges from a PKM system.

Wisdom comes from thinking, from writing, from processing, from lived experience. It comes from the application of knowledge.

For concrete knowledge, the kind our ancestors had in abundance, the knowledge-to-wisdom gap is most often bridged by physical experience. For example, I’ve been doing a lot of reading recently about layering systems for outdoor activities, but until a recent scare at the top of a mountain on a cold December day, I hadn’t fully grasped how quickly you lose body heat once you stop and thus the importance of what is sometimes called a ‘stopping layer’. That wisdom is now seared into my psyche by a combination of adrenaline and energy gels: a lived experience.

For more abstract knowledge, lived experience can be substituted for a more cerebral experience: thinking, writing, discussing — but note that none of this is done inside a PKM system — it happens independently, and more importantly, it takes conscious effort in the here in now.

Notes that you filed away five years ago when you were interested in functional programming are not going to create wisdom in the philosophy of AI, which you are currently interested in. In fact, they are detritus. They are clutter masquerading as knowledge, or worse, as wisdom. Unless you did something with them at the time, they deserve to be deleted.

I think this quote from the video illustrates just how back-to-front the core assumption of this type of PKM is:

To revisit the art of Zettelkasten for a moment, we can look at its historical prodigy: Niklas Luhmann…Proponents of Zettelkasten look at him and say that the key to achieving and producing things like Niklas is to follow his personal Knowledge Management philosophy. However, this is not so. They have incorrectly tied his success to his particular note-taking system. This is the opposite of how it should be. Niklas didn’t find his purpose because he collected a bunch of notes. He collected a bunch of notes because he had awesome things he was trying to do. He was passionate about his field of study. He consumed massive amounts of information, and the note-taking system was produced as a byproduct of it. His passion did not come from the notes—the notes are simply a byproduct of the passion.

First comes the interest, the passion. Then comes the reading, the studying. Then come the notes. Notes are a by-product.

The physical analogy to this philosophy is minimalism. The kind of minimalism I subscribe to doesn’t advocate living in an empty white box — it simply asks us to do away with everything we don’t currentlyuse. There’s no litmus test that works for everyone, but perhaps you might consider getting rid of any item of clothing you haven’t used in a year, for example. In this context, currently is understood to mean ‘within a one-year timeframe’. I like the word current for this use case — it’s similar to its use in accounting terminology: current liabilities, for example, are those that are to be paid off ‘soon’ — whatever that means to the particular business filing accounts, or the tax authority. Keep this idea of current in mind, we’ll return to it shortly.

Here’s another extended quote — the last, I promise; but it’s a good one, and it serves a dual purpose. It’s from Episode 519 of The Minimalists Podcast, where the hosts discuss the subject of clutter(emphasis is mine):

You touched on the sort of subjective experience of clutter. I wish I could give you the list of, here are the 1,000 items. If you have them in your home, get rid of them because these items are clutter. It doesn’t work that way. I might be telling you to get something you truly get value from. So it’s not dogmatic in that sense. It’s not an ideology and it’s not prescriptive like that. Anything can be clutter if it gets in the way. And the hard part about that is there are many things we bring into our lives, material things, but also relationships, careers, cities, that serve us really, really well for a period of time and sometimes for a protracted period of time. And it really adds value, but then it ceases to add value and the value wanes and wanes and then it falls off with the abruptness of a coastal shelf. And then there’s no value at all. And then we look at the thing and say, yeah, but I got so much value from it. And now it gets in the way. That thing wasn’t clutter, but it is clutter now.

The value you gain from a note, like the value you get from a physical item, is completely relative to your current context. If you gain no current value, it’s clutter. Furthermore, what provides value to one person might be clutter to another, and further-furthermore what provides value changes over time as what’s in our current window drifts and morphs. That’s the first lesson this quote teaches us.

The second lesson is incidental. I listened to this podcast episode yesterday. There was no quote in my digital vault that quietly mated with a few others and finally inspired me to write this article. I’ve been thinking about Wisdom vs. Knowledge and The False Promise of PKM for about a month, it’s my currentobsession. Naturally, as soon as I heard this quote I stopped, made a note of it (specifically, I took out my phone and noted ‘minimalists podcast clutter’ at the bottom of this file) and now I’ve used it. There you have it. The note was a by-product of my current area of interest, or as I’m starting to refer to it, the article I’m currently writing.

What article are you currently writing?

PKM for Minimalists

Time for the practical bit. I’m going to propose a system to replace the modern incarnation of PKM, including second brains, Zettelkasten and Obsidian vaults. Here are the commandments:

Decide on the meaning of current for you

Only make current notes

Make them semipermanent, i.e., permanent enough to cover your current window

Don’t stress about them lasting forever

Don’t attempt to create one canonical system — use a combination of convenient systems/devices

Don’t attempt any sort of sophisticated organisation

Notes should be findable when and if you need to find them

In short, there is the why of note-taking, and the how. To understand the how you first need to grasp the why, so we’ll start there.

Current Window

Everything in this non-system revolves around what you are currently interested in. If you take nothing else away from this essay, just remember this: read, write and make notes only about what you are currently interested in. This seems so obvious, but I don’t think many people even stop to consider it. Let me reiterate the question I finished the previous section on and add another: What article are you currently writing? What book are you currently writing?

Maybe you actually write, maybe you don’t, that’s cool — but we’re all currently writing an article. I actually think we’re all currently writing a book too. This is how I conceptualise the current window — a ‘short-to-medium’ timeframe where the ‘short’ is the period it takes to write an article, and the ‘medium’ the period over which one might write a book. Again, you don’t actually have to write articles or books for this to make sense, but asking yourself “What book am I writing?” is a powerful way of elucidating what your true medium-term interests are.

Just remember there is no ‘long term’ in this non-system and that the meaning of ‘short term’ and ‘medium term’ is highly personal.

For me, the metaphorical book I’m currently writing is roughly equivalent to the title of this blog — Paleolithic Principles for a Digital World — thus a lot of my reading, thinking and note-making is dedicated to the topic of how we can regain some of our hunter-gatherer mojo in the modern digital, and increasingly AI-dominated, landscape. I expect this to be ongoing for years, to be honest. This medium-term project is punctuated by brief spurts of deep-diving into other things I’m interested in, like this treatise on ditching PKM, which has turned into a literal article.

Just to reiterate: whether you write or not is irrelevant. Just be aware of what falls into your short-to-medium term current window. An easy way to do that is to be able to say what article and what book you are currently ‘writing’.

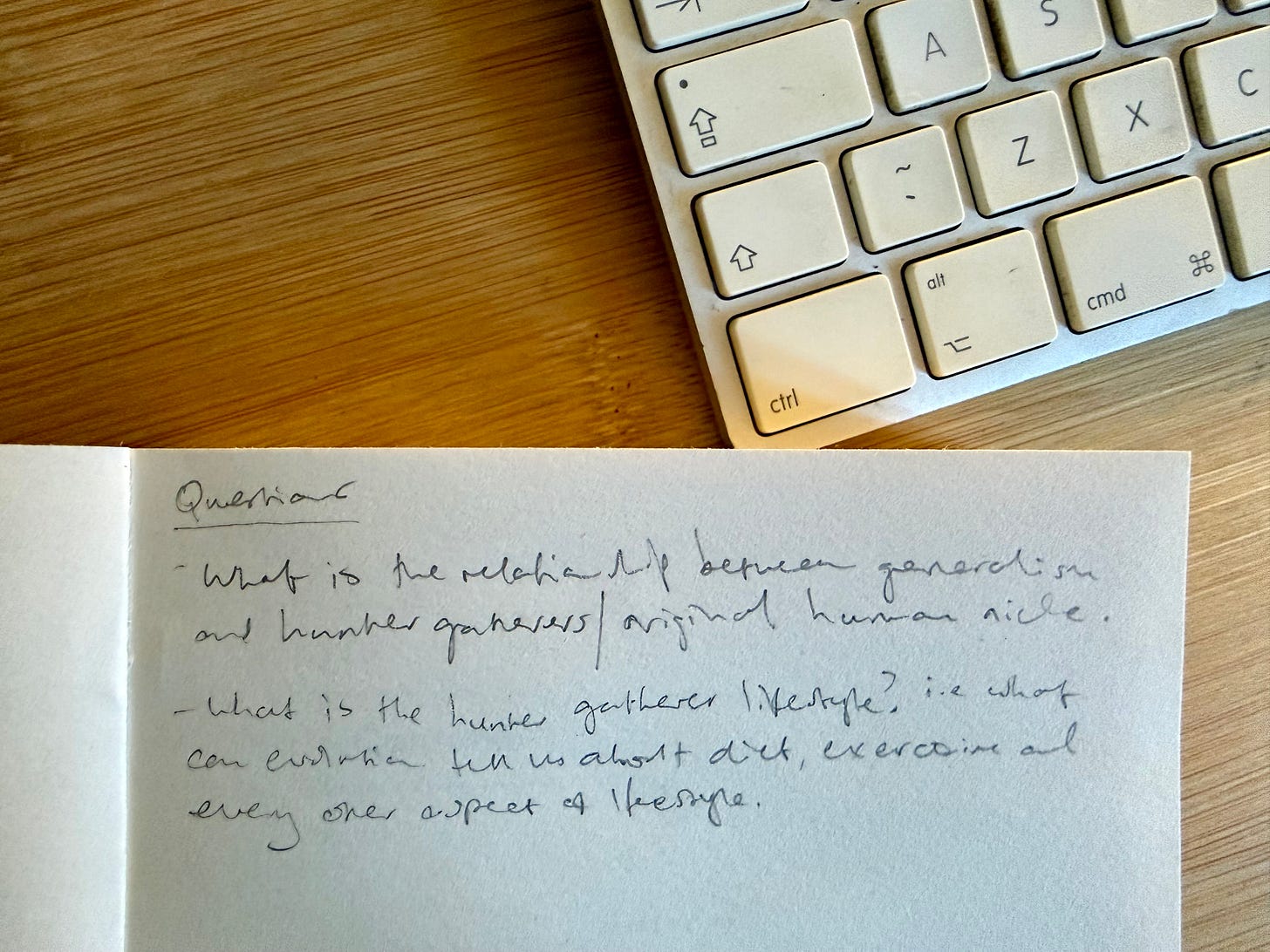

Another of my favourite techniques is to explicitly write down questions. I do this at both the short-term and medium-term levels. Specifically, every time I read a book, I physically write down 2-3 questions inside the front cover that establish what I’m trying to get out of that book. You’d be utterly amazed at the difference this makes in turning you from a passive, slightly disinterested reader into a textual sleuth. When you read with purpose, with a mission, you activate a different part of your brain — instead of scanning for knowledge you are seeking wisdom. This leads to a much better experience all round: more enjoyment, more engagement, better highlights, better retention and ultimately, more wisdom.

At the medium-term level I maintain a simple text file with a list of (currently) six ‘open’ questions. These are the ones pertaining to the ‘book’ I’m currently writing. These are the embarrassingly philosophical questions like “What is the system? How did things end up like this? Was it designed? Did it evolve?”. This is total geek-fest and I’m not going to bore you with the other questions right now; we’ll leave that for another post.

Questions. Questions that are important to you. Questions that preoccupy you now. That’s the crux of it.

A quick aside. I have this nasty habit of buying screws and duct tape in Lidl. You know that section in the middle of the stores that has discount hardware that rotates in and out each week? Every time I go to Lidl I buy two or three packs of basically everything because it’s so much cheaper than buying it at a proper DIY shop. I collect and hoard all these screws, staples, zip ties, drill bits, router bits (!) and rolls of tape with uses as specific as “Fix small cracks in the radiator tubing of your car”. Never once did I spontaneously build a firewood store out of this crap. You know what I did when I needed to build a firewood store? I went to the DIY shop and bought exactly what I needed for my current project.

How to Keep Notes

This is the easy part. Don’t. As in, make notes but don’t keep them (forever). Once you fully accept that notes are made as a by-product of your current work and that outside of that context they are nothing but clutter, you free yourself from many of the burdens of PKM.

Notes need only be retrievable in the short-to-medium term, which means they don’t need to:

Be permanent

Be well-organised

Form a holistic system

In terms of permanence, semi-permanent is good enough. You need to be able to retrieve and review notes during your current window so having them in a notebook or in the notes app on your phone, or both, is great. Having them on loose bits of paper, or on the back of napkins, means they’re going to get lost, thrown away or destroyed too soon. Find a balance between durability and low-friction, but most of all, let go of the notion that your note collection is some sacred body of work that should outlive you. Don’t necessarily deliberately purge notes (or do, if it floats your boat), but don’t get hung up on permanence.

In terms of organisation, nothing more than the ability to find and retrieve is necessary. For example, highlights made in a physical book or eBook are both fine where they are; if you need them, you’ll be able to go to your bookshelf, grab the book that has come to mind, flick through and find the quote. They do not need to be processed into a permanent, organised, canonical reference system. Likewise for notes you make either on paper, or digitally. A notebook is ideal — it is chronologically ordered by nature and serves the purpose of making it easy to locate recent thoughts. The same goes for note apps. PostIt notes are best avoided. Don’t categorise or tag notes — those systems of organisation support the back-to-front model of wisdom creation and assume that you will need or want to consult past notes thematically. Again, you will not look at past notes once they are out of your current window, so chill.

In terms of completeness, forget about trying to discover or build the one system. Out of all the burdens this form of PKM allows you to release, this, I feel, is the biggest. The single, unified, perfect PKM system and set of workflows is a delusion that just leads to wasted time and feelings of inadequacy. Use an ugly patchwork of mediums - notebooks, highlights in physical books, note apps. IT DOESN’T MATTER. As long as you can find it somewhat quickly tomorrow, next month, tops next year, you’re good. Don’t use PostIts, don’t use napkins, don’t use receipts. Don’t have 25 notebooks, have 3.

Remember, above all, that your notes are always in support of your current questions. These will change over time. Your notes are transient.

How to Use Notes

Don’t. The notes are a by-product of your process of converting knowledge to wisdom. The notes are the exhaust fumes from your brain — the harder you accelerate into a question, the more come out.

Four Problems, One Solution

Right at the start of this piece, I stated that this realisation had solved four psychological ‘ticks’ for me. Finally, we’re at the point where I can tell you.

Should I stick with paper books or switch to eBooks?

What should I read next? (and why I don’t want to read AI text)

Why write when no-one reads my stuff?

Which PKM system should I use?

I guess you either identify with these or you don’t. If they sound ridiculously exaggerated and existential, you’re probably not at my level of nerd.

Paper vs eBooks is easy now. IT DOESN’T MATTER. Since I’m not trying to build a single, holistic system, nor am I doing anything special with highlights, I can use both and chop and change between the formats as I see fit.

“What should I read next?” is actually a superb two-for-the-price-of-one. In the most obvious sense, I should read only books and articles that answer my current questions. Anything else is mostly a waste of time. I say mostly, because I don’t read purely for pleasure, so just reading a book for fun is not on my radar, although I understand that’s not going to be how everyone rolls. More importantly, I now have a better grasp on why I dislike the idea of reading AI-generated text so much and am so against using AI at all in my own writing, even for research and brainstorming. When I read, I think. When I write, I think. Basically the only reason I read is to be exposed to someone else’s thought process, the exhaust fumes of their cognitive engine. AI doesn’t think, it just remixes the entirety of humanity’s textual output into a beige soup. Admittedly, it can create prose that is both convincing and great to read, but it’s not true thinking. This is why books like Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations are so important. They are the best kind of book — the ones whose authors never intended anyone else to read. That’s the kind of book I want to read.

It’s also the kind of book or article I want to write. Articles like this. I write to make sense of all this. I hope you’ve sensed that as you read these words. They weren’t written for you, they were written for me. Of course, I’d be overjoyed to know that this has helped you, like Andrew’s video helped me crystallise these ideas that have been floating around in my head for a while now.

And finally, which PKM system to use? I think you already know the answer, right?

None.

Postscript: Knowledge vs Wisdom

Your purpose, as a lifelong learner, is to turn knowledge into wisdom. I see that more clearly than ever now. Perhaps there is tangible output — books, articles, notes — perhaps not. IT DOESN’T MATTER. They are all by-products. Focus on things that interest you for as long as they interest you and then move on. Don’t force yourself to be interested in anything and don’t force yourself to remain interested in something after the initial flame of obsession has flickered out. Only by having clear and currentinterests will your knowledge work yield the ultimate prize: wisdom.

I enjoyed this, I’m off to change the ‘note’ on the chalkboard on the back of the kitchen door, it’s not current enough!!

I was excited and looking forward to some vindication when I read the title. I’ve had two friends trying to onboard me to PKM for a few years, but never managed to organize myself enough. And seems like I never have to!

But then you went and shot down my favorite notetaking strategy - jotting down thoughts on napkins, letters, or whatever paper is closest. It created great artwork where shopping lists sat next to startup ideas lying under papers that mingled doodles from the last zoom meeting with reflections on the meaning of life. I really think you need to give that system a serious try.

I guess the one thing I did get from skimming “how to take smart notes”was to have notecards with me when I sat down with an important book and only write down important thoughts. It’s given me another pile of disorganised papers, but the notecards do have a higher signal to noise ratio.

In the end, I think writing down thoughts is part of the thinking process. It doesn’t matter how I do it cuz I’m not going to read much of it again anyway. But writing it down helps etch it in my brain.